When the Granny Clock Chimes

A Journey to Purpose without Grandchildren

Note to our readers

When I began writing this essay about my experience as an older woman without grandchildren a couple of months ago, I had no idea just how timely or provocative the topic would become. At that time, vice presidential candidate Tim Walz hadn’t yet accused his opponent J.D. Vance of being "weird," and I was unaware that Eric Weinstein had referenced the grandmother hypothesis in a 2020 interview with the same Senator Vance, claiming that “the reason human women survive past menopause is to serve as grandmothers and great-grandmothers.” When this interview resurfaced last month, it sparked a heated debate, with some on the far left—ironically, many of them men—labeling the hypothesis as misogynist, despite its well-established standing in evolutionary biology circles.

To my mind, dismissing the profound ways in which our biology influences and governs our lives is both bewildering and unproductive. Acknowledging these biological truths doesn’t diminish our agency; rather, it enriches our understanding of the roles we play as members of the human species. This essay explores the evolving role of the modern grandmother, moving from the traditional (OG) roles to the unique and powerful position we hold today in WEIRD societies. KLD

I’ve been thinking a lot about grandmothers lately. Mostly because I’m not one, but I’d like to be. I suspect I am part of a growing cohort of Western women whose children are not reproducing or have never had children themselves. Young women talk about their biological clocks that tick ever louder as their fertility cycles wind down, and I’m beginning to think there is a similar evolutionary alarm that rings for grandmothers. Deep within our bellies lies a pain that for some of us, is noticeably sharper as we begin to age out of grandmotherhood. My son is 41 and although technically there is still time (and hope) for grandchildren, I hear my grandmother clock’s chimes beginning to toll. I don’t know if it’s all in my head or if my hormones are reacting to the overall absence of young humans in my life, but I know that something feels off.

I was born in 1963, which makes me part of the second generation of women who benefited from reliable birth control and for whom obtaining a college education and achieving financial independence were not only possible but expected. My grandmother, born a little over a century ago, faced a very different reality. When she married in 1940, she quit her telephone operator job to help my grandfather run his mining business while she raised four children. When they were mostly grown, she reclaimed her independence by taking an office job she loved. She worked outside of the family enterprise only for a short time—soon her daughter needed her for a new role: grandmother

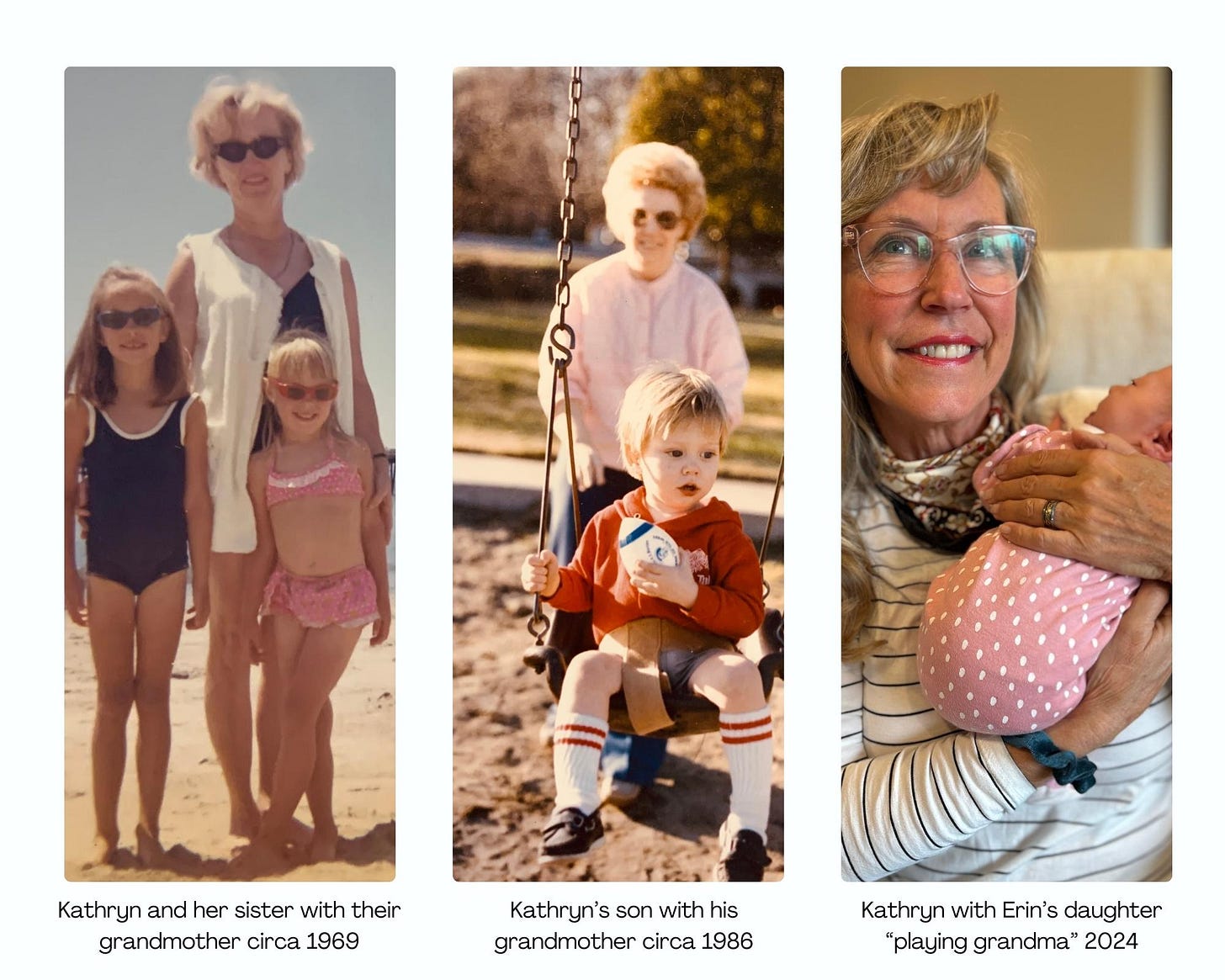

In 1968 after six tumultuous years of marriage, my father walked away from his family, leaving my high school educated mother utterly alone with two young girls and no financial support. Had my grandparents not been able to provide a home and economic resources, the odds of our growing up to be well-adjusted adults would have been substantially diminished. Instead, my sister and I had relatively stable childhoods in a multigenerational home until my mother remarried many years later. Although my grandmother eventually worked part time again, we were clearly her priority when we were young.

As I was lamenting the idea that I may never be a grandmother myself and thinking about the important role both grandmothers played in my life, I became curious about the role of grandmothers throughout history and during a deep dive into the literature happened upon an interesting hypothesis. Apparently, the female human reproductive system is unique in the animal kingdom. Only a few other species (whales, elephants, giraffes and Japanese aphids) live well beyond their reproductive years. Most other mammals continue to produce offspring right up until the bloody end. Chimpanzee females, for example, live to about 60 and can still birth offspring at 59.

This piqued the curiosity of researchers in multiple fields and eventually led to The Grandmother Hypothesis which posits that becoming bipedal a few million years ago came with a significant price tag: a narrower pelvic opening that helped keep our innards in but limited the cranial size that could safely pass through the birth canal. A way through this evolutionary bottleneck was smaller, less developed neonates who could make it safely into the world without killing their mothers, although childbirth remains a risky business to this day. Because little humans come into the world somewhat unfinished, they are particularly vulnerable and dependent for a longer period and require a higher level of parental investment than other species. Given the demands on parental resources, particularly in early environments where finding food and avoiding predators were constant challenges, the support of additional caregivers became crucial. Enter Grandma.

First put forward in 1957 by George C. Williams, one of the most influential evolutionary biologists of the 20th century, the Grandmother Hypothesis has continued to gain traction through the years. In the 1980s respected anthropologist Kristen Hawkes’s work with the Hadza, a hunter gatherer tribe in Tanzania, produced convincing evidence that grandmothers increased the reproductive success of their offspring which in turn ensured the continuation of their genetic lineage. Beyond Grandma’s help with food foraging and care for her grandchildren, apparently, she also plays an important role in the form of cultural transmission. Understanding social customs, local knowledge and cooperative behaviors are essential for survival and integration into the complex social structures of human societies.

In traditional cultures where grandmothers are still offering this service, these “OG grannies” are recognized and valued for their knowledge and care, and often influence community decision making. The Council of Thirteen Indigenous Grandmothers is one such group of women. Meeting for the first time in 2004 at the Dali Lama’s retreat center in New York, these women hail from around the world, meeting as a council every six months to preserve and share grandmother wisdom.

In contrast to OG grannies, most of us in the developed West are WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, and Democratic) grannies. Evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich coined the term in 2020 in his book “The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous.” He argues that one of the most prominent features of WEIRD people is that “they prioritize impersonal pro-sociality over interpersonal relationships.” This seems to hold true for many modern grandmothers in the west. If we’re lucky enough to have grandchildren, many of us are not willing to step away from our careers to invest in our childrens’ offspring and the rest of us are simply unable to afford to leave our jobs to care for grandchildren.

By the time I was a young single mom, my mother was a fully independent working woman and not able to leave her small accounting business. She adored her grandson but even if she could have swung it financially, I’m not sure she would have been satisfied taking care of one grandchild full time. At 41, she was a young granny and after spending her youth raising her daughters, she understandably wanted to spread her wings.

My ex-husband’s mother, on the other hand, was a bit older and bridged the OG and WEIRD granny worlds. Although she had worked as a civil servant for many years, she wasn’t exactly a career gal who loved her job. When she retired with a generous pension, she wholeheartedly embraced the role of caregiving for her young grandson. Grandpa also played an important role in my son’s upbringing, but it was grandma who was there for him after school with a kind but firm hand, to help with homework and provide nourishing meals. Once again, because a granny came to the rescue, the grandchildren in our lineage were able to receive the benefits of living in a nurturing kin unit.

I am sad to report that my son may be the last of his kind in our family. If he had requested my granny services for his own children when he was in his 20’s or 30’s, I wouldn’t have had the time or financial resources to step away from the company I founded. And if I’m fully transparent, like my own WEIRD mother, I’m not sure I would have been satisfied being a full-time caregiver at that point in my life. Now that I’m older and my son seems to be opting out of fatherhood, I am feeling a deep and unrequited yearning for grandchildren just as the hands on my granny clock near midnight. So now what? What happens when we step out of ancient evolutionary cycles and skip investing in offspring, or in our children’s offspring in such a short time? What evolutionary adaptation might mother nature dream up for grandmothers who no longer “grandmother?”

My hunch is that grandmothers still have an important role to play in the health and well-being of the next generations. But I also think that we need to get busy rethinking what that role might be, because as far as I can tell the world is not an especially kind place for older women who aren’t contributing to our species in a meaningful way. Cultural memes can be incredibly cruel for those of us who have aged out of market economy metrics that value beauty, youth and economic productivity. Labels like "Hag," "TERF," "Karen," and the more recent "Childless cat lady" have all been used to demean older women, particularly those who are outspoken.

Further exacerbating the situation, coming of “granny-age” in a time of rapid societal and technological change can be downright daunting, and in the absence of traditions or rituals that honor “the change” or help us define new roles, it’s proving hard to find our way. The shifting cultural landscape has eroded the familiar landmarks that once guided older women, leaving us to navigate a world where traditional paths no longer align with the realities of modern life. This lack of direction can lead to a sense of disorientation and a diminished sense of purpose as we grapple with how to age meaningfully in a world that often overlooks the value of our experience and wisdom. It's no wonder, then, that older women are among the largest consumers of antidepressants, as they struggle to redefine their identities and find new meaning in this stage of life.

But it doesn't have to be this way. In fact, WEIRD grannies are much more capable of navigating this journey than they might realize. We have more education, wealth, independence, and access to quality healthcare than any group of women in human history. The lives we lead now are ones our great-grandmothers could only have dreamed of, an important perspective to keep in mind when lamenting the lack of young humans in our lives or wondering what to do with ourselves post empty nest. Plus, we have nature on our side.

Something truly remarkable happens on the other side of menopause. As our estrogen wanes and testosterone rises, we experience a surge in confidence, clarity, and courage, often accompanied by a newfound sense of vitality and resilience. We emerge as new beings, and if we’re willing to recognize and embrace this transformation, we may uncover a renewed sense of passion and vigor lying just beneath the surface. I would argue that finding our way to our inner matriarch and learning how to cultivate our own unique version of grandmother wisdom is mission critical to the health and well-being of our human family. This idea was revelatory for me, sparking new levels of creativity, and a burning desire to leave this world better than I found it for future generations.

Once we’ve made it through the passage and found our new voice, we WEIRD grannies need to get busy thinking about how to show up for our young people. For starters, we can use our accumulated skills and experience from the market economy, regardless of what sector we’ve worked in, to influence policymaking, business practices and philanthropy. We can invest time and/or money into initiatives that support a sustainable future, and we can mentor the next generation of young people as they step into families and societal leadership. Last but certainly not least, we can help our youth navigate this tumultuous time simply by listening and offering deeper historical perspectives than may be presented in school or in the media.

There are many examples of WEIRD women using their market economy status to improve the lives of others. One of my favorites can be found in Sweden, where 46% of elected officials are women. There, a new program has recently been implemented that allows some of their generous parental leave benefits to be transferred to grandparents willing to provide care to their grandchildren. A Nordic market economy solution by WEIRD mothers (and probably plenty of granny aged women) to support those willing to take on OG granny roles, and in turn helping the next generation in a truly meaningful way. I get goosebumps imagining the unstoppable force for good that could be unleashed if OG and WEIRD grannies were to join forces.

I grew my company from my 40s into my mid 50s and as tempting as it was to put my newfound badass business matriarch to work in yet another company, I realized that that time had come and gone for me. This new self of mine, although in many ways more courageous, is also gentler and calmer and more interested in young people than ever before. My journey into granny-dom culminated with the formation of Hearth Matters, a nonprofit that leverages my years in the food business into models intended to improve the economic and cultural status of householders and mothers.

This decision led to meeting my cofounder Erin Szuma, a young mom-to-be who unexpectedly has become a bit like a daughter I never had. The feeling that I might in some way be of use to her or be able to help her new family has brought more happiness and inner peace than I could have ever imagined. On a recent visit to her I found myself holding Erin’s newborn and almost immediately, I felt my granny clock come to a gracious and gratifying stop. As a sense of wholeness set in, I realized that this is how grandmothers through the ages have felt while holding the future in their hands.

I suspect all women come equipped with an OG granny clock, whether they recognize it or not. Perhaps I feel mine ticking louder than most because my familial lineage is literally dying out and there’s not a damn thing I can do about it. The pain of this realization is soothed in part by realizing that beyond the fate of my individual DNA, there is a broader human family who might benefit from an entirely new form of WEIRD and wonderful grandmothering.

I keep thinking back to something the Dali Lama said at the 2009 Vancouver Peace Summit. During a discussion about the progress of Western women and their potential to lead efforts in promoting values that could help solve global challenges in the future, he said “Western women will save the world!” I'm pretty sure he was thinking about both OG and WEIRD grannies when he uttered those words.

Loved this.

Beautiful post Kathryn. A few years ago I wrote an essay exploring the grandmother hypothesis and the older woman's societal role. I loved reading your take on this very important topic. In the last two years especially I have felt my energy shift fundamentally towards this same direction. I needed that time after my own children to create some kind of a career and expression of myself at that moment. Now I am increasingly finding myself moving back to the core--my family and tending this patch of earth. I spent the last 6-weeks helping my child's family welcome their second baby. I lived in a rocking chair with this wee human (when not cooking for everyone) and it felt good.